The story of Joe Gock written by Lily Lee 18 April 2016. This story is extended from the story of Joe and Fay Gock in ‘Sons of the Soil’, Lee and Lam, 2012, pp 411-418. It has been compiled from interviews with Joe and Fay Gock at Pukaki Road, Mangere conducted by Lily Lee, 10 & 22 April 2007, 27 April 2015, 18 April 2016.

Gock Moo Lok (郭武樂)

Joe Gock’s father: Gock Loy Fat 郭來發 (1900-1982)

Gock Loy Fat 郭來發 from Jook So Yuen, Zhongshan was the only child in his family. He had a forefather Gock Chin and a close relative Gock Loy Joe. As a young man he left the village and went to work for Wing On in Hong Kong. In the department store he helped to stack shelves and sell merchandise.

On 8 June 1920 Gock Loy Fat under the name Kwong Sing arrived in Auckland on board the ‘Maheno’ from Sydney. The name was from the papers he purchased in Hong Kong in order for him to obtain a permit to come to New Zealand.

In New Zealand Gock Loy Fat had village cousins from Jook So Yuen. He was related to Jack Choy (Gock Jerng Choy), Norman Choy’s father; brothers Kwok Chong Way and Gock Chung Wah; and Kwok Lai Chuen, father of Laurence Gock (Gock Shek Young).

His son, Joe Gock said that his Dad was an adventurous person. He was interested in flying and in the early years joined the Auckland Aero Club.

In the 1930s Gock Loy Fat started gardening in Clive, Hawke’s Bay, under the trade name of ‘Chong On’ with Gock Sun, and a Seyip villager, Lee Bak.Gock Loy Fat’s wife, Yee Young Hor (余欣好) from Mui Ping (梅 平), Zhongshan, arrived in Wellington, with their 12 year old son (born 1928) Joe Gock (Gock Moo Lok 郭武樂) as war refugees in 1940. Joe doesn’t recall much about the boat trip on the Taiping except that he was dreadfully seasick during the three weeks. He remembers Mrs Young Hoy (Lee Way Hing)1 from Larm Tien, Zhongshan who was in a different part of the boat. She would come up to chat and sometimes swap meals.

Knowing no English Joe attended Mangateretere Primary School in Whakatu for four years before leaving to help his father in the market garden.

According to Joe, the Chong On garden wasn’t very productive and the partnership broke up in 1943. In 1944 Gock Loy Fat leased 12 acres (also at Clive) using the name Kwong Sing, the name he had used in coming to New Zealand. Gock Loy Fat grew a variety of vegetables such as potatoes, peas, carrots and beetroot. For the war effort he grew celery and cabbages. They used a horse for cultivating and scarifying until they bought their first tractor, a McCormick Deere, in 1945.

In 1949 businessman Norman Choy (Gock Yet Wai 郭日維) suggested to Gock Loy Fat to move to Auckland where there was a greater demand for vegetables and better prospects for the future. Joe said that his father decided to take a trip to Auckland to make a preliminary survey.

Establishing a garden in Mangere

When the Gock family first arrived in Mangere it was still largely a rural area. The land was used for dairy farming interspersed with mixed farming, with smaller blocks of orchards, greenhouses, poultry and market gardens. The schools were classed as ‘country service’ for teachers. There were very few shops and the International airport was yet to be built.

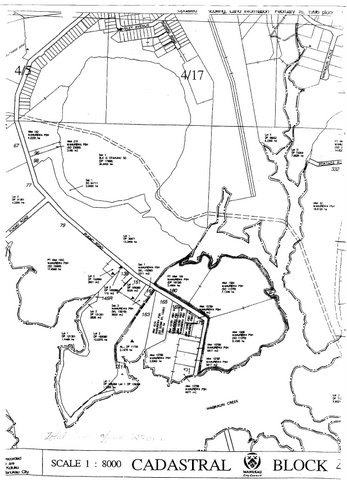

Meanwhile Jack Turner, of Turners and Growers, heard that family was looking for a place so he sent his employee George Yew, to scout around for a garden. He found 72 acres of leasehold land in Pukaki Road, Mangere Central, being market gardened by Sam Lee, from Jung Seng County, Guangdong.2 Joe’s father paid 4000 pounds for the leasehold, which included a cottage, an old tractor and a couple of horses. People at the time thought they were rather foolish paying such a high price for a leasehold block.

The market garden was on rich volcanic soil at the end a peninsula on the northern shores of the Manukau Harbour. Located at the end of Pukaki Road it was next door to a thriving Maori community around the Pukaki marae. Te Akitai Hapu of Te Waiohua were descendants of Hoturoa, captain of the Tainui canoe. The tribe settled here very early and the area was named ‘Te Pukaki Tapu o Poututeka’–the Sacred Spring of Poututeka. The surrounding creeks and estuaries provided seafood and water access to the Manukau Harbour as well as safe shelter for canoes. But much of the land was lost after the 1860 Waikato Wars with only 160 acres left for tribal use.

Photo of Pukaki marae and estuary bordering Joe Gock’s land. Note broccoli in foreground and Mangere airport to left of picture, 2007. Courtesy LILY LEE.

A view of Pukaki crater looking south to the Manukau Harbour. Joe Gock’s market garden and other gardens on southern rim. Courtesy NEW ZEALAND HERALD, 3 March 2007

The Pukaki lagoon crater – the oldest crater below sea level in the southern hemisphere had been acquired by the Auckland Harbour Board in 1911 and was leased by George Henning who was then president of the Auckland Automobile Association. He had the crater drained and used the almost perfectly circular shape to form a speedway circuit which attracted a crowd of up to 9000 at the first meeting in 1929. When the Auckland Harbour Board was dissolved the Pukaki crater was taken over by the Manukau City Council who handed control back to the Pukaki Maori people.3 In the late 1930s the Prangley family leased the old Pukaki lagoon crater of 36.3 hectares as well as purchasing 26 hectares of freehold land.4 Kung Tin, a well known gardener from Hoi Ping first leased land for market gardening on Pukaki Road in the 1940s and later purchased 50 acres of land.5

Kwong Sing & Sons

Joe and his father under the trade name Kwong Sing began to gain widespread acclaim for their innovative growing of vegetables. First, it was a challenge going from 12 acres in Clive to that of 72 acres in Mangere. Joe says:

We were growing a lot of cauliflowers and cabbages at the time and we seemed to be doing quite well. Unfortunately, the whole place got club root from growing the same crop in the same place too often. So it took us about two years to put it right!

But soon after the initial setback Gock Loy Fat and Joe became well known in the markets for the sheer volume and range of produce they were able grow.

Gock Loy Fat was fortunate to have son Joe work with him through the early years and then in later years younger son David Gock (Gock Moo Yuet 郭武悦) also helped run the business which became Kwong Sing & Sons.

David was born in Hastings in 1941 and helped in the market garden from an early age. After completing his secondary school education in 1959 David joined the family business.6

David with his practical knowledge and experience also contributed to the success of Kwong Sing & Sons. David remained in the business until the early 1970s when Joe commenced market gardening under his own name. During his commercial growing years David was involved in the wider community of growers and gave his time willingly to the Auckland branch of Vegfed (now known as HortNZ). He took a leading role in the association and was elected as President of the Auckland branch in the 1960s.7

Picking Peas

In the early 1950s growing peas was very labour intensive and preceded the period of affordable frozen peas. Fortunately there was a ready labour force to pick them right next door at the Pukaki Marae. Joe elaborates:

We grew a patch of peas and we couldn’t even finish picking one or two rows of them after a day’s labour. You got to have that extra labour to grow them. In the beginning, all the Maori at Pukaki Road picked peas and made a living out of this garden. Even then, there were not enough pickers, so we had to go to Ihumatao marae and get their relatives to come over, and then further afield to Panmure. That’s when Jack Sue8 and his gang of friends helped. In those days, peas were something that needed the labour, and the Maoris welcomed that labour.

The picking of acres of peas was the start of a close involvement with the Pukaki Marae and friendships with Maori families, which for Joe Gock has continued over sixty years.

Growing Brussels sprouts

The garden was soon going to change from growing peas and cauliflowers. It was time to try something else. In 1956, Joe married Fay Wong (Wong Way Gin 黄蕙娟) whose parents had a fruit shop in Epsom. Fay, too, like Joe arrived with her mother as a refugee, but from the county of Sunwui in 1941. Fay didn’t know anything about gardening but she threw herself into the work on the family market garden. Kwong Sing became one of the first in Auckland to grow Brussels sprouts. Fay and Joe describe how they came to grow Brussels sprouts:

We went away for our honeymoon in Oamaru and we saw the sprouts growing down there and we thought right, we are going to grow Brussels sprouts in Auckland. (Fay) The grower in Oamaru happened to know my Dad. He said, take some seed home and grow some Brussels sprouts. They make good money. We got hold of an American seed catalogue and we grew the American variety. (Joe) Everybody said, these sprouts are good, where did you get them. There were no seed merchants here that had them. For many years, we had that market to ourselves. (Fay)

Deaconess Eileen Wong talking to Yee Yun Ho in late 1950s. ARCHIVES RESEARCH CENTRE, PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

Picking Brussels sprouts. Eileen Wong Toi talking to Fay Gock in the late 1950s. ARCHIVES RESEARCH CENTRE, PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND.

Carrots and Parsnips

The Gocks grew carrots and parsnips from the late 50s to the 70s. Each season they grew 20 acres of carrots and five acres of parsnips. They bought a tumbler machine for washing carrots from Graham Turner for 300 pounds and used it for 10 years. Turners and Growers wanted the vegetables for their 1kg soup pack (an idea they picked up from America) but it didn’t take off at the time.

Pumpkins

The soil was exceptionally good for growing and the Gocks started experimenting with the growing of pumpkins as an early summer crop.

Each year the Gocks would select the best pumpkins for seed until they felt they had perfect pumpkins with their smooth, glossy grey skin and deep orange flesh. Joe talks proudly about his father’s innovation:

We always harvested our pumpkins before the Chinese New Year in late January. A week or two before harvest time Dad would write ‘恭喜發財’ (Happy New Year) on some of the pumpkins. He scratched it on with a nail while it grew and when it heals over, it sticks out. At that time of the year, at auction, the pumpkins were very early and expensive. They used to put each one on a shelf and sell it by the line or two lines. If you wanted to buy the pumpkin with Gung He Fat Choy on it, you would have to buy the whole line. You just can’t buy one pumpkin.9

For a number of years the Gocks would send away thousands of pumpkins – at least two truckloads a week during the season. Joe, said, that he believes his father was the first in the world (in 1958) to scratch a name or character onto the surface of a pumpkin. The same idea was used in China but not until many years later in 2004.10

Growing Seedless Watermelons

The Gocks decided to grow the big cannonball variety of watermelon. Fay Gock says that they kept quiet about the name of that variety:

Anyhow our neighbour wanted to grow them but couldn’t find the seed anywhere. So what he did was buy a couple of our big watermelons, ate it and used the seed. The following year, he was growing them, but they still weren’t as big as ours.

Once they had become successful at growing their cannonball watermelon others followed. But the Gocks always wanted to go a step further, which lead them to the ‘seedless watermelon’. Joe says:

We were going to experiment and produce seedless watermelon seed, when we saw this magazine that they were already selling seedless watermelon in America, we followed it up and found out which seed merchant sells them. We bought seed off them and started our own.

The new seedless watermelon was first noted in the New Zealand Fruit and Produce magazine in April 1958. The article said that a sample melon was displayed in an Auckland warehouse and that it was eight inches in diameter and weighed five pounds. It had a sweet, pink centre and only a few tiny white seeds, which [Mr. Joe Gock] pointed out would not be in melons harvested later in the season.11

They were one of the few commercial growers to grow seedless watermelon successfully and according to Bruce Coleman, horticultural adviser of the Department of Agriculture, ‘this is a botanical achievement of no mean merit.’12

A ‘first’ with Stickers

It was said by Jack Turner, that at that time, Joe was the only one he knew about in the world who placed stickers on their produce. Most of the fruit and vegetables that came from overseas only had the brand name on the carton, nothing on the fruit. At the time the watermelons were put on racks and sold individually at the auctions. Fay explained that it was necessary to put stickers on ‘for the simple reason, we didn’t want the seedless one to get mixed up with the seeded ones.’ Joe explains:

A lot of buyers complained and said, ‘Joe we bought your watermelon but it’s got seed in it’. But the carrier had got it all mixed up. So the only way to do it was to put seedless watermelon stickers on it. At the time nobody could print the labels. We tried everywhere. We managed to find someone – J Allen, the calendar guy- to print them for us. It was simple, so simple. It was white cello tape with our name printed on it. And away we went.

Joe stopped growing seedless watermelons when there was a change in weather conditions. The climate was a lot cooler during the growing period.

Kumara King

The Gocks main crop from 1952 and for the next 50 years was kumara. They started growing kumara from spare kumara plants given by Hiko Raniera Wilson who lived next door with her children, Mahia, May, Elly, Joseph, Barbara and Ellen.

This neighbourly act led to a long lasting friendship between the Wilsons and the Gocks and when Joe increased his kumara production he was able to provide ample employment for many of the whanau. They have built up a lot of mutual respect through the years and Joe says, ‘every time there is a wedding or a tangi (funeral) we go to the marae and they put us at the head table. They treat us well’.

Once kumara growing got underway the Gocks grew their own plants from selected tubers – provided by the Department of Agriculture. The Gocks then provided their strain of disease-free stock to Bruce Coleman, of the DSIR for testing and research. When in the 1960s the Northern farmers in Dargaville and Ruawai13 were devastated by the ‘black rot’ disease in their crops, it was the Gocks who agreed to provide their good, disease-free kumara stock to be used. It was given the name Owairaka Red by the DSIR.14

Joe driving tractor using new harvesting machine in 1958. Gock Loy Fat (left) unknown (centre) and Fay (right) watching machine in action digging kumara. Courtesy JOE GOCK.

Owairaka Red kumara packed in apple boxes in the 1950s. Courtesy JOE GOCK.

From left: Virginia, Jayne and Raewyn with very large Owairaka Red. Weight of one large Kumara on scales was 11lb, c1960s. Courtesy JOE GOCK.

The Storage of Kumara

In the 1960s the Gock family grew more kumara than any other market gardeners in New Zealand. But storage was a problem. An expert with the DSIR Horticultural Department, Doug Yen15 suggested they pilot a prototype-curing shed, which would hold about 500 cases of kumara.

Encouraged by their experiment with curing and storing kumara through the winter months and supported with an 8000 pound loan from their bank manager the Gocks took up the challenge of building a large curing and storage shed. The shed contained eight rooms, each 15 feet by 20 feet. It was specially built with air-conditioning equipment, temperature and humidity control.

When we put the kumara in the room -when it was full- we needed to heat it up to 85 degrees for one week. That would cure and heal up all the wounds. Straight after that, we bring the temperature down to 65 degrees and hold it at that temperature. Humidity is about 85%. If the humidity is not high, then the kumara will shrivel up. That humidity would keep them just right.

This method based on an American design reduced kumara crop loss from as much as 50 per cent to less than one percent; and a crop of 250 tons could be held to disperse to markets as required. Joe looks back and recalls, ‘In those days people thought we were mad to spend 8000 pounds to build a kumara shed. They thought with that money he should build a block of flats and sit back and collect the rent. What they didn’t know was 8000 case of kumara, we sold it for 3 pounds a case, so we got our money back in one crop.’

From Kwong Sing & Sons to Joe Gock

In 1975 the family business stopped trading as Kwong Sing and Sons as Joe and Fay Gock used Joe Gock as their trade name. Joe and Fay had three daughters Jayne, Virginia and Raewyn who all helped in the garden. Joe’s father and mother were close to retiring but still continued to help Joe. Gock Loy Fat died at age 82 in 1982. His wife Yee Yun Ho died at age 98 in 1995. They are buried at the Mangere Lawn cemetery.

Joe and Fay Gock carried on the market gardening on the same site and increased the acreage by buying blocks adjacent to the original leased land. They grew on 140 acres of market garden land and continued to experiment and meet new challenges.

Broccoli in Polystyrene Boxes

The Gocks gave up growing watermelons in the 1980s and decided to try their hand at growing broccoli. The concern for them was how to send it to the South Island where it was fetching $60 per box, while retaining its freshness. They were searching around for a solution, when Joe spotted a polystyrene box in an overseas magazine:

… it so happened we could get that box here. Later on that company decided to close down. We got another company to make it for us. This company said, ‘you are the only ones that are using it now, we don’t think it’s worth us making the dye to make the box for you’. They think it’s too risky, making it for us one year and the next year we may not want it. So I asked him how much it costs to make the dye. He said $8000. And I said, ‘okay, I will pay for it. You give me the royalty at so much per box’. He gave me 50 cents per box. And we got it back in one year. We are not putting broccoli in boxes now but we are still collecting royalties.

Joe explains that the broccoli is cooled to take all the field heat out, and then it is packed in polystyrene boxes, first with ice on the bottom and then with ice on top of the broccoli before the lid is closed tight. It becomes ‘just like a portable cooler’ says Joe. The ice was purchased from the company Party Ice, a ton at a time. The company even supplied a freezer to hold the ice. Some retailers like George Chan Ltd purchased broccoli directly from the Gocks to export to Japan, Hong Kong and Australia, but their main market was the South Island.

Muscat Alexandria Grapes

Joe and Fay Gock have grown grapes for a number of years. They purchased the 10,000 square feet glasshouse and the Muscat Alexandria grape vines from Turners & Growers in the 1980s. Joe explains:

Turners decided to sell up. Money was tight because the market crashed. They lost the kiwifruit business, so they decided to sell up [the grapes] and we bought it and decided to grow them. Ted Turner said to pull the whole thing out, grow tomatoes instead. There was more money at the time in tomatoes. But we decided, no, we are not going to do that, we are going to keep it.

Fay and Joe consider the grape superior to the Muscat Italia, which is slightly larger. They believe that the Muscat Alexandria is the ‘world’s best eating grape’ but they had to convince the customers:

When we started selling them the buyer don’t like it because it’s too small. It’s not as big as the Italia. They said the taste is good, but it was too small. They wouldn’t pay the price. So we came up an idea of telling what the auctioneer to say to the buyer. All right the auctioneer said, ‘Which one would you rather have, Mother Teresa’s good heart or Marilyn Munroe’s good looks? You can’t have it both ways’. In the end, they started to buy them. It didn’t look as good, but it tastes better.

Fay in cutting vines in the greenhouse, 2011. Courtesy MEGAN BLACKWELL

Grapes packaged ready for market, 2007. Courtesy LILY LEE

Growing Rhubarb – a Backyard Hobby

Fay’s backyard hobby of 40 years has now become the product with the greatest potential fetching $200,000 per year for six acres of rhubarb. At first they grew a few clumps for themselves, and then they tried increasing this. Fay says ‘you just can’t sow the seed readily. I can increase my amount, but anybody else that wants to jump in will have a hard time’.

In the past the Gocks have purchased plants from Coopers, Winstone’s, and Yates. They planted them altogether in the same patch but ‘they did not seem to do any good’. ‘Then’, Joe says, ‘one year we found one good one so we kept that and it kept multiplying. We are not sure which one, we kept growing the whole lot together every year and comparing. Out of all that, we just found one good one and it’s been increasing.

Fay continues:

We’ve been planting it for a number of years. More than I care to remember. At one stage it was very disheartening. Nobody wanted it; it was just a weedy plant. All of a sudden, people dropped out and the rhubarb price went up. Now only Trevor Bridges and me, and there might be one more that is growing rhubarb for the whole of New Zealand commercially. Now the silliest thing is, Japan wants rhubarb. England wants rhubarb. Everybody wants it and can’t get enough of it.

In September and October 2007 the Gocks exported their rhubarb by air-freight to England in their polystyrene boxes weighing only half a kilogram and costing less to send than the wooden or cardboard boxes. Joe says:

At that particular time of the year, England don’t have any rhubarb. The importer from England wants some more. There is a big supermarket that sells it over there. He’s specified polystyrene boxes. When he got them there he said ‘Oohhhh, it’s just like garden fresh. It’s in perfect condition!’

The Gocks had several more requests from the export market, one for frozen rhubarb by the ton and another from America for the finished product: rhubarb pie. ‘But’, says Fay, ‘Fresh Direct has taken a lot of the work out of it. They get our rhubarb, they chop it all up and sell it all tidied and sell it by the tub. It’s expensive, but who worries. The housewives buy it by the tub $3.11 or round about.’

And to their surprise in England the importer wanted to get hold of the roots. But Fay was adamant, ‘I said no. I’m not parting with my roots. I will sell you all my rhubarb but I wouldn’t sell you a root.’

Growing in 2007

A visit to Joe and Fay Gock’s market garden in 2007 showed they had reduced the amount of land they cropped to 90 acres with 50 acres leased to a European grower of mesculun. The fact that they were still actively involved in gardening in spite of being in their eighties was impressive. The writer describes the visit:

Fay drove us around the 140 acre property and pointed out the various crops in progress: 20 acres of broccoli and cauliflower planted -‘but not the hybrid type!’ says Fay. 30,000 red and green capsicums near ready for picking; 10 acres of dwarf beans; 10 acres of golden kumara ready for digging; and the 10 acres of Cos lettuce at various stages of growth. Fay showed us the 6 acres of rhubarb and a patch of taro leaves16 by the dried up creek. They had five employees and Joe was on his tractor weeding.

Fay cutting cos lettuce for vistors in 2007. Courtesy LILY LEE.

Fay Gock holding Louisiana Gold kumara, 2007. Courtesy LILY LEE.

In 2007 Joe Gock still using the Lilliston weeding and moulding machine he purchased in the 1950s. Courtesy LILY LEE.

Of the golden kumara Fay says that they only grew about ten acres for family, friends and a local processor ‘Prepare Produce’- an Air New Zealand catering company. They would like to keep the strain going but disappointingly for them there is no one commercially who wants to grow this strain of golden kumara -the Louisiana Gold kumara- which they think is superior in taste.

Joe and Fay Gock -Innovative Market Gardeners 2016

In 2016 the property is now one of the last remaining blocks of market gardening land in Mangere. Joe and Fay are still growing acres of cauliflower, cos lettuce, capsicums, rhubarb and Owairaka Red kumara as well as Louisiana Gold. The soil remains very fertile and very productive. In recent years he has shown many interested groups around the garden including a group from America. ‘The kumara still grow to a large size,’ said Joe. ‘People could hardly believe they grow so big so the editor of Grower magazine who was visiting in 2009 gave me a certificate to prove it!’

Their three daughters Jayne, Virginia and Raewyn lead their own lives do not wish to take up market gardening. It is hard to say what will become of the garden. But Joe and Fay are very positive. They would like to hand their garden down to someone who is interested in growing. But Fay says philosophically, ‘what shall be, shall be’.

In October 2013 granddaughter Megan is married to Saul Blackwell. Courtesy COLIN WONG

Four generations of Joe Gock’s family, from left granddaughter Emily Brageul and great granddaughter Christine Brageul, wife Fay Gock and daughter Virginia Wong, Sep/Oct 2013. Courtesy MEGAN BLACKWELL.

Both in their 80s Joes feel very ‘blessed’ to have been a market gardener:

‘No matter what you do, if you treat human beings or plants with tender loving care… the plants will grow better’. ‘Sum Seng See Sing 心想事成- whatever you dream can become your reality.’

Fay adds: ‘I’ve always said, why follow everyone else. I rather go one step ahead and do it yourself and everyone else follows you.’

They have worked physically hard all their lives but they have never indicated that they are hard done by. They have approached life positively and with a sense of humour. They have no regrets says Fay: ‘The only regret is that we’ve got aches and pains. That’s not because of the garden. That’s because we are getting old. But…if you didn’t get out there, you might get worse. Once you get out there and do things and walk around you forget about your aches and pains.’

Return to Village

Joe Gock has returned to his village of Jook So Yuen a number of times and generously donated to various village projects. ‘I went back in 2010 and 2012 as the house needed renovations,’ said Joe. He also went to remove the family urns as the local authorities were putting a road through the cemetery. ‘I had to move the urns twice!’ said Joe.

Talking about Jook So Yuen, Joe said, ‘The Wing On descendants have built two hotels in the village now. Gock Man Joe and his wife who are direct descendants still live in Hong Kong. The village people have rented their land out to be cultivated by poorer families from other parts of China’.

Conclusion

Joe Gock has contributed in many ways to community organisations. He has been wholehearted in everything he supports giving generously with donations and koha. He is and active member of the Auckland Chinese Commercial Growers Association, the Auckland Chinese Community and the Auckland Zhong Shan Association. He has donated money and produce to local schools and local marae. He has a strong religious affiliation with the Sathya Sai Organisation founded by Sathya Sai Baba.

Joe Gock, a man of great humility and strong character has been recognised in China by his village elders and government officials as a person who has achieved success as an overseas Chinese ‘wah kiu’.

In New Zealand, Joe was acknowledged as an innovative grower – with the highest horticultural award – the Bledisloe Cup in 2013. He also gained national recognition and was awarded the Queens Service Medal in 2015 for his outstanding services to the community and to horticulture.

Reference

- Mother of four children born in New Zealand: Norman, Jack, Andrew and Richard Lum.

- Sam Lee aka Lee Ling, arrived from China in 1920. His nickname was “Ai Jay Lee” (Shorty Lee). Sam’s wife Kawerongo Aupaki (from Whatapaka) was brought up by the Wilson family of Pukaki. They had 8 children. After leaving Mangere Sam Lee market gardened at East Tamaki in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Through their Pukaki Maori Marae Committee.

- In 2007 after fifty years the Prangley family were selling the lease and their freehold property.

- In 2007 the land was sold to European growers of mesculun.

- Note that while David Gock was an integral part of the Kwong Sing & Sons, however, the writer’s story focuses on Joe Gock and the story is told from Joe’s perspective.

- David has a son Kevin and two daughters, Marie and Roseanne with his first wife Beverley (nee Wong).

- Lowe Jack Sue was from Woo Jow Gerk in Zhongshan. He spent a lot of time with Maori families at Panmure.

- Personal communication by Joe Gock to Lily Lee 18 April 2016

- Michael Chong, of Fresh Direct found the etching onto melons and pumpkins in China in 2004.

- Fruit and Produce, April 15, 1958, p. 11.

- Newpaper article feature under The Rural Scene, about 1962. Joe Gock private collection.

- The Northern growers provide nearly 100%of the commercially grown kumara in the 2000s.

- Owairaka was the location of the DSIR that conducted the testing of the plants. The ‘Red’ was the colour of the kumara. It later changed to a purple colour in the Ruawai soils of the North.

- According to Joe Gock, Doug Yen collected up to 300 varieties of kumara. When he left the department they were acquired by the Japanese. Doug Yen lives in America and still corresponds with the Gocks.

- Alongside the house is a small low lying area. A few years ago Fay decided to buy $60 worth of taro to throw into the ground there. Now they sell taro leaves at $8 per kilo to Pacific Islanders who use the leaves for their umu feasts.